Anna Stone, Group Archivist, on keeping people honest by preserving Aviva’s 325-year-old archive.

Anna Stone, Group Archivist, on keeping people honest by preserving Aviva’s 325-year-old archive. Others describe it as the most important insurance archive in the UK but for Anna, it’s ‘like a third child’.

First it was, can we prove we’ve insured a swordsman? Then an acrobat. The most recent one was a fireman. So, I've been going back through policy registers looking at people's occupations. Helping with concepts for Aviva’s 325-year anniversary is a good opportunity to unearth interesting stories.

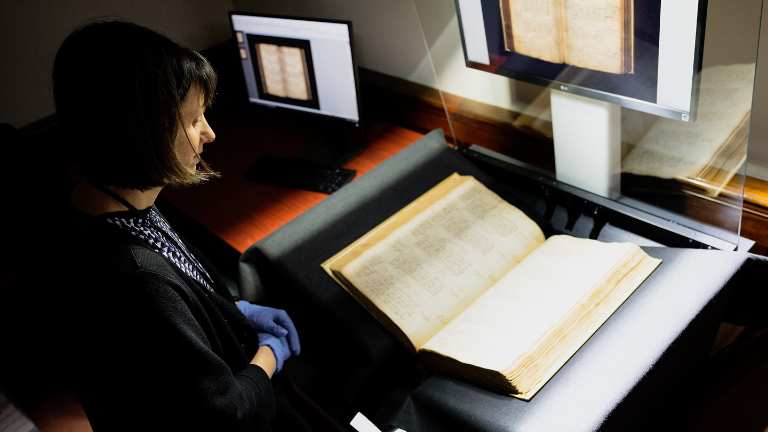

Policy registers are kept in great big books. I rest them on a cushion to protect the spines. I don't usually wear gloves when I'm looking things up in the registers because they can sometimes increase the risk of damage. Clean hands are good enough.

On life not going as you hoped

Growing up, I wanted to be a marine biologist. I liked rocks and rockpools.

Then I did a careers test at school, and archivist came up. I have A-level Latin – which is helpful for looking at old deeds – a history degree and an MA in archives.

My mum has really bad handwriting. She used to leave us notes and we’d say, ‘gosh, how can we work this out?’ Palaeography, the study of handwriting, is a discipline of archiving and so it’s like she was training me from an early age. It’s proved very handy.

Mum took me to work and kept me in a basket under the desk. For me, it was never a weird thing to be a working mother, which also turned out handy. My own children were three and nine months when I became a single mum. I look back now and think, how on Earth did I do that?

Dealing with a new baby was like ‘gosh, I don't know anything’. If I’d dreaded every Monday morning, that would’ve just been terrible. But I got a sense of myself from the fact that I can do my work well. In that way, I would have been lost without it.

On shaping the future

I began looking after the Aviva Archive in 2000. Archivists look after the history of a company – we are its memory. I feel like it keeps people honest. Going back to the records and being able to say, ‘this is the truth, and this is why this is the truth.’

There’s the fun side of the job – finding interesting stories or advertising images, and sharing those things on social media, or with our media and communications teams.

And then there's another side, which is maintaining a record of what Aviva has said. If we need to prove we told our customers, shareholders, or colleagues something, then we've got a record of it. Nothing goes out from us about our history that I can't substantiate.

My first boss said, ‘any old person can keep things. It takes an archivist to throw them away.’ When records are up for destruction, we will say what we want to keep. And so we shape what is left in the future for people to see what life is like today.

On dust, cardigans, and scandal

When you tell people you’re an archivist, usually you have to say – which I don’t like doing – that it’s a bit like being a librarian. Thinking back, when I took out insurance with Aviva, archivist wasn’t listed as an occupation. I had to select librarian.

I belong to an archivist group – members regularly complain when archives are shown in films as being dusty. And there’s a misconception that a lot of us wear cardigans. That's another thing that gets archivists a little bit annoyed, though I wear cardigans and I don't mind.

People don't think insurance archives are very exciting. I used to work for Guinness and people thought that was exciting, but their archive wasn’t as interesting to me as Aviva’s. It was full of lovely advertising but not the interesting stories behind things.

There was a scandal here back in 1823. I found it going through early Norwich Union Life board minutes from the Dublin branch: the board were adamant they wouldn't pay out on the insurance of the poet, Percy Shelley, even after they received proof of his death.

I wanted to know why. Being able to solve problems like that, it’s a bit like being a detective but not having to deal with any of the horrible bits. Turns out, the insurance had been taken out by some money lenders to secure a loan they had made to Shelley. As he was underage when he took out the loan, the insurance should never have been allowed. Having turned down the claim, the board did return the premium to the money lenders - with interest.

On never-before-seen photographs

I’m proud of creating the Book of Remembrance.

We gathered all the names of everybody we could find who worked for our companies and were killed in the First or Second World Wars. It was a lot of looking through old newspaper reports, a lot of research, then we brought it all together into one big book of everybody’s names.

Families come to Aviva specially to see their relative’s name. They’re touched we remember their great, great uncle or great grandfather who worked for us over 100 years ago. That feels really good, and it's something that didn't exist in the archive, even in little pieces. Now it’s there for the future.

A few times, we've had a photograph of someone who worked for us and the person who writes to ask us about them has never seen that relative. In those days, most people didn’t have cameras.

And we've got letters from families of men who worked for us and who died, particularly in the First World War. People wrote to us saying, ‘he would have done well with you, our hearts are broken.’

There are sad stories in the archives, but I’m glad we’ve got them.

On working in the dark

One day each week I get the scanner and my colleague, Tom, moves to another room. We can't both be in the same room because when you're scanning documents you can't have changes in the light. We have the blinds down and the overhead lights off.

Cambridge University are training computer software to read the handwriting in our policy registers and turn it into printed text which can be searched by computer. To make this work, we have to keep shadows off the pages and scan each page in exactly the same light.

We’re scanning entire books of 4-500 pages – touching pages one after the other, so we wear nitrile gloves. Once you get going, you just keep going. If you put your book away, it's hard to get the book back in exactly the same place on the scanner.

Scanning wasn’t available when I trained as an archivist. You had to get a photographer to do it, turn books upside down and squish them onto a photocopier (which you should never do because you risk damaging them) or transcribe them by hand. But now we've got these fantastic things.

I’d like to be better at looking after electronic records. Tom knows a lot more than I do, and it's going to become increasingly important.

On leaving things better than you found them

On a Saturday evening, I might sit down with my son and watch a Marvel film, but I will also be going through scans from the week and looking up interesting people. I'll shout out ‘Peregrine Fury!’ and he'll say, ‘great name - it'd be a good Marvel character.’

There are so many things you could investigate and not enough hours in the day. I want to leave the archive better than I found it, and that will take all my working life. I don't want the archivist in 50 years to look back and say, ‘why has that been allowed to crumble into dust? Why wasn't it taken care of?’ So no, I don't think I missed my calling as a marine biologist.

***

It takes our people to make Aviva a great place to work. For more on life at Aviva, follow us on LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter.